I’m going to do a bit of yapping, so if you want to skip to the good stuff, click here.

A Year (Not) in Embedded Engineering

In February 2022, I began my software engineering career as an Associate Software Engineer at Canonical. I was working on Mir: a window manager, compositor, and display server for Linux. Admittedly, I didn’t know too much about any of those things when I was hired. I knew about Wayland; I knew it was a protocol for writing display servers, but I didn’t know much more than that. In fact, I’m not sure that in February 2022 I was capable of telling you what the difference between a window manager, compositor, and display server were.

I first started using Ubuntu in 2010 on a hand-me-down Dell Inspiron from my mom. Specifically the 10.04 release, Lucid Lynx. As a 10 year old kid, it blew my mind that people could write an entire operating system and maintain and distribute it at no cost to the user. Even more, Ubuntu turned a single-core Celeron laptop which was borderline unusable on its original Windows installation to a blazingly fast machine that I could customize to my heart’s desire. I loaded that thing with Compiz effects until its fans were begging for mercy.

This laptop, almost just another brick in the wall of laptops at the recycling center, became my daily driver with which I explored everything the FOSS community had to offer.

Getting to work with the people who made that crucial childhood memory a reality was quite intimidating. Here I am, a fresh computer science graduate from Louisiana, in a hotel in Frankfurt playing Codenames with the lead of Ubuntu Desktop. I felt incredibly under qualified working with the people whose names I had read in About pages twelve years prior.

The team who worked on Mir are some of the most brilliant minds I’ve ever had the pleasure of meeting. They pushed me to be the best software engineer I could be. I call 2022 the year I experienced “trial by fire”. The team couldn’t have been more patient as I floundered my way through PRs. The code reviews that year were master classes.

Despite the patience and helpfulness of the team, I needed to work on something different. My ability to write code was improving, but the problem domain was something that I was not very familiar with. I decided that if I was ever going to enjoy the process of growing as a developer, I’d need to work on a project that was particularly interesting to me.

When Worlds Collide

As far back as I can remember, I’ve had a tendency of getting quite hyperfixated on things. After Linux it was jailbreaking iOS devices, then it was softmodding Wiis and OG XBOXes, while that was going on I was playing guitar in a rock band, then it was PC building, making YouTube videos, DJing, expanding my musical palate, then software development, the list goes on.

Reflecting on this, as much as I seemed to be a completely different person every few months in my middle school and high school years, I really was just oscillating between hyperfixating on one of two interests: computers or music. Sometimes both at the same time.

In my senior year of college, I decided that what I really wanted to do was work on making tools for musicians with computers. I applied to several companies and got some good advice on starting my career from many people in the industry, but no job offers.

This wasn’t very shocking. I rarely saw new grad positions opening up for software engineering jobs in music technology, so I was applying to positions I was completely unqualified for. Understanding that C++ was the go-to language in the industry, I applied to every job that I was qualified for who used C++ in their stack, which got me that first job at Canonical.

With a year of experience on my resume, I applied for every software engineering position I was even remotely qualified for at every audio technology company I could think of (about 35 companies total).

Fender, who had an embedded software engineering position open, interviewed me for the role. I had an Electrosmith Daisy that I had very minimal experience with, but outside of that, I had zero experience with embedded systems. Between interviews, I was cramming every search result I could find for I2S, I2C, UART, SAI, STM32, SPI, GPIO, and the other various acronyms that were in the job listing.

After getting the job, I was in “fake it ’till you make it” mode for months. Luckily, while working in a domain that interests me with incredible mentors who helped me get up to speed with the world of embedded engineering, the impostor syndrome that I’ve felt since entering the workforce has started fading way. I don’t get everything, but I get it.

How To Become An Embedded Engineer

If you’re trying to pivot into embedded engineering, you’re in luck. There are some incredibly high-quality and free resources to get you on track.

Here are some of my favorites (in no particular order):

- Vivionomicon’s “Bare Metal” STM32 Programming series

- Arguably the single most helpful writing I’ve come across on embedded programming. Walks you through many of the features and design considerations one will come across when using STM32 products. He also gets into the nitty-gritty on how CubeMX (STMicroelectronics’ code generator for STM32 projects) generates peripheral access code and clock configurations. Also, his breakdown on linker files were incredibly helpful in demystifying them.

- Stargirl Flowers’ The Most Thoroughly Commented Linker Script (Probably)

- Exactly what the title says. Great for people who know nothing about proper memory utilization and layout details on embedded systems, such as myself about a month ago.

- (This post gets bonus points because she works on synthesizers)

- Makefile Tutorial

- Not specific to embedded programming, but Makefiles were as confusing as linker files to me until reading this

- Low Level Learning on YouTube

- Some of the most entertaining and digestible videos on embedded and systems programming

- Let’s Get Rusty on YouTube

- Not necessarily focused on embedded engineering, but a good channel to have in your toolbelt if you’re curious about Rust

Some Things I learned

The point of this post isn’t to be a course on embedded engineering, but I wanted to share some things I learned that I didn’t know before entering this field.

1. Peripherals

You’re almost certainly going to have some kind of peripherals connected to the device you will be working on: buttons, screens, speakers, LEDs, potentiometers, Bluetooth SoCs, proximity detectors, and so on.

The first thing you’ll need to learn about is how peripherals transfer data from themselves to your MCU (Microcontroller Unit) and vice-versa. Your MCU likely has ADCs (analog-to-digital converters) to convert analog inputs into data you can work with, DACs (context clues) to convert digital signals generated with the MCU into analog voltages you can send to other peripherals, then it’ll have digital transport interfaces to transport different types of digital data to and from the MCU: SPI, I2C, I2S, USB, UART, and a few more. It’s important to learn what all of these are, what kinds of data they’re used to transmit, and have a general understanding of how they all work.

2. Clocks

One of the cool things about working on embedded devices is having direct control over multiple clocks. I imagine every software engineer knows that their PC’s CPU runs on a clock, and that the clock affects the speed of the device, but in the embedded world, you get access to many more hardware clocks. These will be used for synchronizing data communication between external chips and the MCU, determining the rate that ADCs are polling analog data, controlling Pulse Wave Modulation (PWM) which is how you’ll end up controlling LED brightness, and much more.

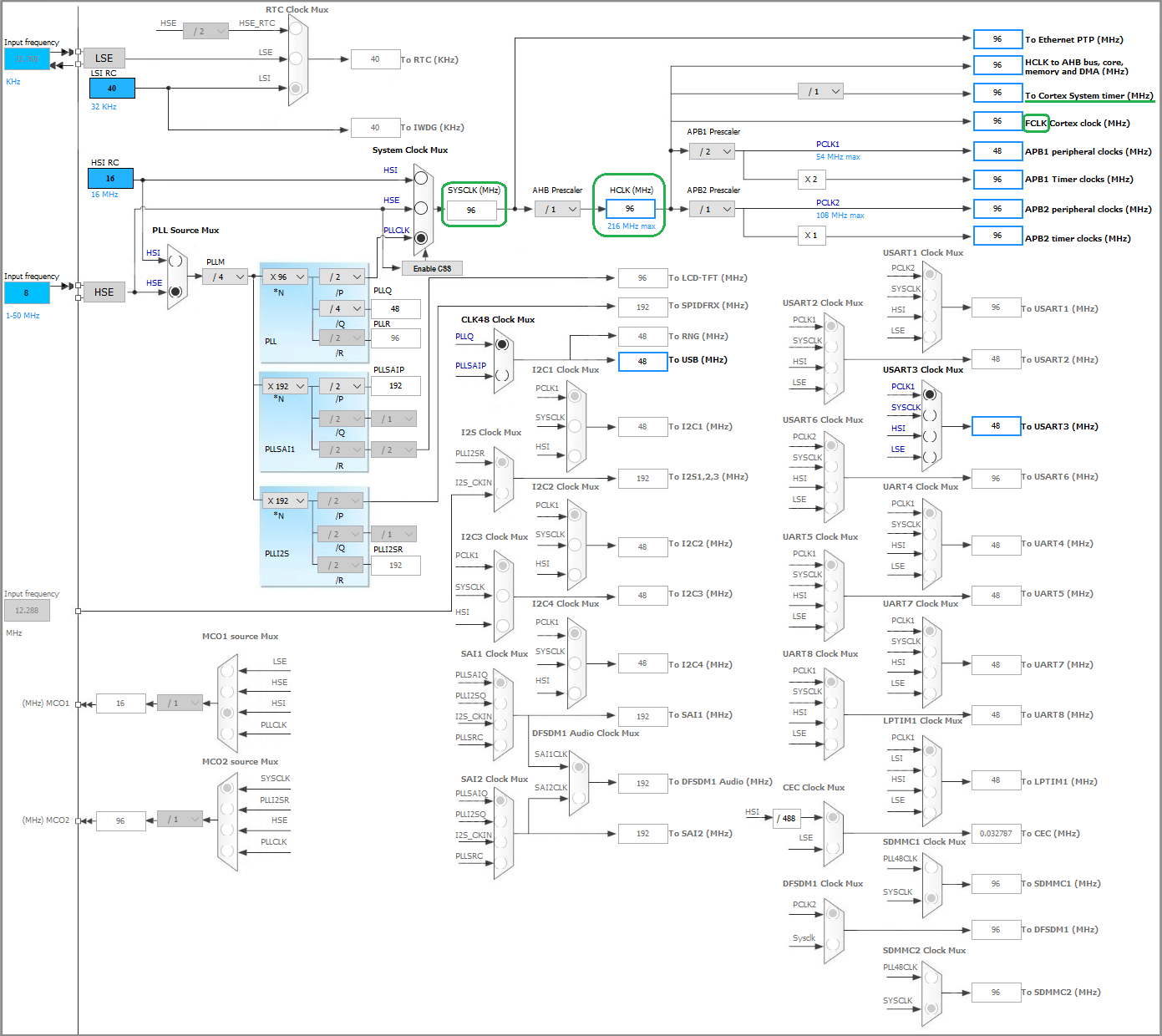

On many STM32 devices, the peripheral clocks are controlled by one master clock which is then divided down into multiple subclocks. These subclocks can have their frequencies either divided or multiplied to get to the frequency you need them to be. If you’re using CubeMX to generate your MCU configurations, the Clock Configure page can look wildly confusing, but once you understand why it’s laid out that way (because you have clocks which are subdivisions of other clocks) it starts to make a lot more sense.

Image lifted from K. Mulier on Stack Overflow

Image lifted from K. Mulier on Stack Overflow

3. Interrupts

Think about this: analog signals can happen really quickly. Really quickly. Blink and you missed a thousand of ’em.

Your application that has a main loop which gets run every millisecond could never catch something that fast.

That’s why we have hardware interrupts which can run a function in your code instantly after an analog signal is detected.

You may be thinking, “Wait, but what happens when my precious main loop gets interrupted?” Well good news: the MCU can freeze the stack where it’s at, create a new stack to run the interrupt callback function on, then jump back onto the original one once it’s done. Neat!

As awesome as that is, there are some things you need to keep in mind when using hardware interrupts:

You’re going to be getting pulled out of your main app context every time one of these interrupts are hit, wherever you were in execution. So you want whatever code is in the interrupt callback to be something that can get executed quickly so your code can get back to what it was doing.

(This one lead to one of the most confusing bugs I have ever seen.) If your hardware interrupt callback function needs to access a piece of data that gets initialized at startup, keep in mind that the interrupt may happen before that thing is initialized. So if you had a class/method like

Power::shutDown()andPowergets initialized inside a class namedMain, if your callback hitsMain::powerSwitchOffCallback()which callspower.shutDown();keep in mind thatpowermay not exist yet! Otherwise, your callback is going to hit a function pointer to nowhereland, and maybe this only happens 1/100,000 times the callback is hit because hardly anyone flips the power switch back off within the first 5ms of the device booting.

4. Timers

MCUs will often have hardware timers which can be used to send a clock to peripherals or run callbacks at regular intervals. If there’s anything that is time critical in your application where you need to guarantee that code will be run every {period of time}, a timer can call an interrupt which pauses all other execution to run that code.

5. RAM Layout

My favorite thing about embedded engineering is getting full access to the system’s resources. No pesky OS trying to tell me how my processes are scheduled or how my memory is paged. This gives you the ability to do a lot of cool optimizations without the worry that an OS will come in and have some behavior that makes them impossible.

You get full control over what gets placed where in memory. Sometimes, you’ll be working with an external RAM or FLASH chip, and you’ll need to be careful about what data goes there for access time/memory capacity reasons.

6. DMA (Dynamic Memory Access)

Instead of having to pause your code to stop and listen to retrieve or send a packet to a peripheral, you can use on-board DMA controllers which can always be copying data from a digital transport into a region in memory, which your application can then read when it’s ready to read the received data.

This is an absolute necessity when quickly and consistently transporting streams of data.

Epilogue

Embedded software engineering is a very interesting field. There is something exciting and “real” about having so much control over hardware. Working without an OS or a very simple RTOS gives you full confidence that if something isn’t working, it’s your fault, and if you know the system well enough, you’ll know where to go to fix it.

…most of the time.

Debugging software on low-power hardware with limited FLASH space, especially if you need to disable some debugging optimizations to make it fit on your hardware, is a real hassle sometimes. Debug prints are quite expensive operations, and if you’re trying to solve a problem that’s affected by time, the debug prints may be too expensive.

All of this, though, will teach you a lot.

Dean Ween, of the rock band Ween, once said the following when asked about why they were recording their albums themselves on four-track cassette recorders instead of in a professional studio:

When you only have four tracks to record on, you have to write better songs…

Limitations can be the greatest teacher of all. The domain of problems you have to solve are so immediate, so tangible, that you know you can find the answer if you look hard enough. I believe you can truly become one with your system, at least more so than you ever could with the thousands of different devices with different operating systems and CPU architectures and displays and input devices that are all capable of rendering this website.

If you’re a software engineer, especially early in your career, and you’re thinking about giving embedded a shot, I highly recommend you do.